Building A Village - Part 2.2

Lessons from My Journey

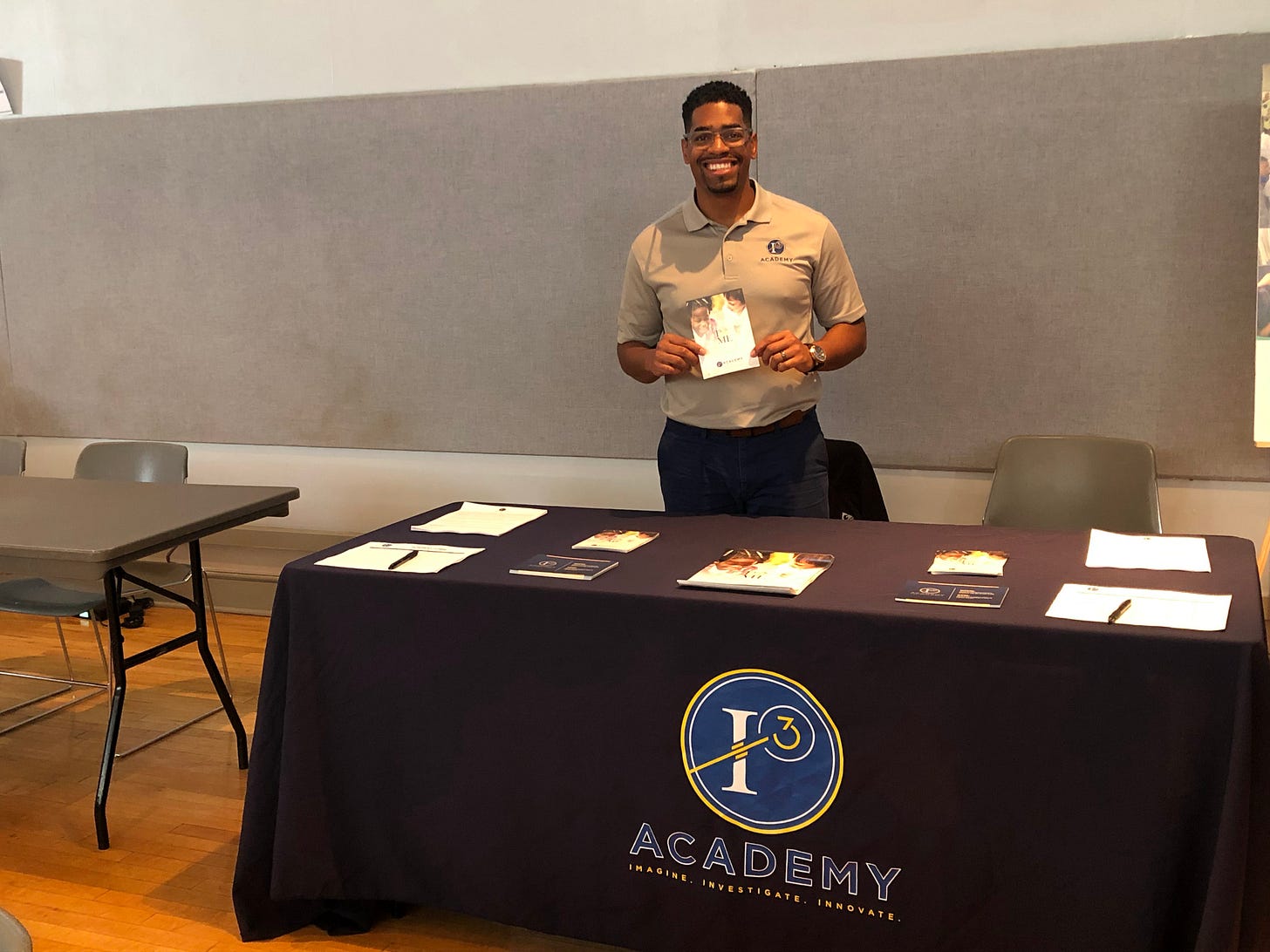

Public Charter Schools vs. Traditional Public Schools. This argument has raged for the last three decades. There is much to debate about the merits of each opinion, but for me, at least at that time, I’d grown to believe that charter schools provided an opportunity to build something better. Out of my disillusionment grew a desire to create systems and …